Mass media is incredibly pervasive in our society. Constant and readily available, it consumes our everyday lives. Arguably the most powerful source of information in this day-in-age, the media bombards our society with notions of good versus bad, desirable versus undesirable, acceptable versus unacceptable. These types of discourses are particularly evident and distressing in modern media’s deep-seated racial bias in its portrayal of African American women. More specifically, the obvious Eurocentric ideals in most of popular media render only African American women who have been constructed to fit these ideals as beautiful, causing an entire group of African American women to be deemed invisible, unacceptable, and unworthy of the media’s attention.

While we can only speculate the intentions of the media, these particular patterns of racial bias constantly emerge. In this paper, I will explore the history behind the very strict set of ideals that decree only certain African American women “beautiful”, and how the media’s perpetuation of these standards are consumed by and of African Americans, causing some disconnect in the African American community between those women who fit more into the Eurocentric ideal and those who do not. While there is no doubt that the dominant culture excludes certain African American women from their realm of beauty, the ultimate internalization of Westernized standards of beauty by other African Americans causes certain women of darker skin and coarse, “kinky” hair to feel ostracized even by their own race.

In order to attain a complete understanding of this complex issue, we must first asses one of its fundamental components: the history that created the deep-seated biases and attitudes about skin color that exist outside of and within certain African American communities. Discrimination based on skin tone within a racial group, known as Colorism, is one of the many legacies from American slavery (Stephens & Few 253). The racism that occurs amongst African Americans as a people is arguably a direct backlash of slavery, concerning the division of the two kinds of slaves: “house Negroes”, who worked in the master’s house and “Field Negroes”, who performed the manual labor outside. This separation was enacted based on the slave trader’s beliefs that darker skin inherently meant better labor, whereas lighter-skinned Blacks were thought to be better suited for more intelligent tasks and lighter labor (Kerr 273). Furthermore, an overwhelming majority of enslaved Black women who worked domestically were of lighter complexion, as often times these women were raped by their masters who saw lighter-skinned Black women as more handsome and delicate (Kerr 273; Baptist 1621). In D. Channsin Berry and Bill Duke’s documentary film Dark Girls, one woman states that during this point in history “we as a people were so disenfranchised that we adopted some of that… a lot of that” (Dark Girls). This marginalization that began with slavery has continued amongst both the wider population and other African Americans. Eventually, “European scientists began to categorize the appearance of Blacks in the New World, including hair and skin tone” that was dominated by fair skinned and straight haired people (Thompson 833). Once black beauty was juxtaposed with White beauty, a socially stratified hierarchy began to take shape, placing darker-skinned, “naturally” coarse-haired African Americans at the bottom.

As scholars Dionne Stephens and April Few examine, this hierarchy created by the ecopolitical institution of American slavery has evidently continued to the psyche of contemporary African Americans (Stephens & Few 258). Traditionally, those who posses skin color or hair that more closely resembled that of Caucasian Americans were/are more likely to be given higher status in American society. This internalization of such standards is made clear by studies like the Clark Doll test, conducted in the 1930s by African American psychologists Dr. Kenneth Clark and Dr. Mamie Clark. The Clark Doll test was conducted by asking African American children to express certain preferences for black or white dolls, with questions such as “which doll is the dumb doll?” and “which doll is the ugly doll?”, while the only difference between the set of dolls was the color of their skin. The majority of the African American children who took this test selected white dolls for the positive attributes, and the black dolls for the negative (Bernstein 197). This internalization of what the larger society sees as good, acceptable, and beautiful is demonstrated through this test, which has been replicated numerous times, even in recent years. It is clear, therefore, that “African American children learn about the significance of skin tone when and if they see people treated better or worse based upon having lighter or darker skin” (Stephens & Few 253). This internalization of “good” versus “bad” skin tone based off of Westernized ideals is problematic, as it marginalizes an entire group of African Americans. As one girl in Kiri Davis’ documentary film A Girl Like Me states, “Since I was younger I also considered being lighter as a form of beauty or… more beautiful than being dark skinned, so I used to think of myself as being ugly because I was dark skinned” (A Girl Like Me). The pain experienced in some individuals’ present has everything to do with this collective past (Rooks 281). Today, these deep-rooted forms of Colorism directly translate into modern day notions of African American beauty both beyond and within Black communities. In our society, more specifically, the media’s perpetuation of these historical standards through its portrayal of African American women continues to be consumed by and of the larger society.

Media images shape our conceptions of race by constantly bombarding us with strict, Eurocentric standards of beauty. The mainstream definition of beauty “consistently includes immutable qualities found far less frequently among populations of African descent” (Sekayi 469). The image of Black beauty in popular culture reflects the ideals of typical Westernized beauty, giving this narrow definition a race-based measurement for what is considered “good” and “bad”. As scholar Dia Sekayi highlights, “when black women were (and are) presented, they typically met (meet) Eurocentric ideals in terms of… skin color and hair texture” (Sekayi 469). Though famous, beautiful African American women like Halle Berry, Beyonce, Oprah, Rihanna, Janet Jackson, Tyra Banks and many others have achieved high-status in American culture, media representations of these women display images that have become increasingly “whitewashed” over time. As one 21 year old, African-American woman on Harvard’s campus (who shall remain anonymous) stated in an interview I conducted with her: “I’d like to see different kinds of black people represented in the media. It’s always a light skinned woman who has a certain look – they basically try to make her look white in any way possible”.

The two main characteristics, as scholars have found, that are increasingly “whitewashed” by popular media are African American women’s hair and skin tone. Famous African American women such as those described above are typically featured in the media with lighter-colored, straighter hair, lighter makeup, and sometimes even digitally altered skin tones. A clear example of the media whitewashing images of African American women is seen in Beyonce’s 2008 L’Oreal ad campaign.

This image of Beyonce has clearly been Caucasianized, as she is pictured with long, straight blonde hair and a skin tone many shades lighter than her natural tone. Tying back to the roots of such alterations, “these two characteristics have historically been used as measure of social, political, and economic worth for African Americans” (Stephens & Few 257). Such ideals are incredibly oppressive for a large number of African American women, as they see such alterations done and are indirectly told that their natural self is not acceptable. The more Westernized African American women look, the more beautiful they are to be considered. More so than ever, African American women are confronted with these very strict, Eurocentric images of African American beauty presented in mainstream media.

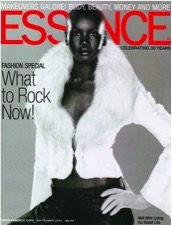

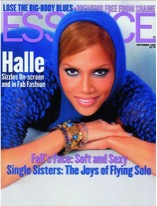

To complicate this issue a bit, I examined three sources that challenged these Eurocentric standards of beauty that are so prevalent in the mass media: A blog called Beauty Redefined, and Ebony and Essence magazines. The blog Beauty Redefined, though highlighting many of the major points of this issue, I believe cannot be seen as a major complication to or compelling force against the dynamics at play between the media and black women. As a one-time, one-read blog post, this article (though presenting worthy information and could possibly serve as an empowering read for women of color) does not stand as a significant challenge to the enormous amount of power and prevalence of mainstream media. Ebony and Essence, on the other hand, represent black media that was created by and for African Americans (Essence being specifically targeted towards African American women), and serve as a continuous source of information. The subversive work within these magazines often does work against America’s larger culture of whitewashed standards by highlighting issues, personalities and interests specific to African Americans in a positive/self-affirming manner. These sources directly seek to empower African Americans. Relating specifically to African American women and beauty ideals, Essence magazine solidifies this notion by nature of having a more varied section for female hair – including Natural, Relaxed, Transitioning, Wigs/Weaves, Celeb Look, and Street Style. The very existence of these sections serves as a better representation of the realities for African American women than mainstream media almost ever poses.

However, to complicate these ideas of subversion even further, psychologist Maya Gordon examines that, “several scholars have argued that the beauty ideal presented by Black media and promoted in the Black community is just as narrow as the mainstream ideal” (Gordon 246). This argument does not seek to delegitimize the amazing work done by these sources, but rather addresses the idea that even if African American women do not ascribe to or identify with mainstream media ideals, a very strict set of ideals is still present in certain African American media. Ultimately, many African American women in the United States are never fully “protected” from White Western norms of beauty, as seemingly “Black subjectivity has no existence without comparison to White (mainstream) culture” (Hesse-Biber et. al 709; Thompson 855). An illustration of this Western-influenced bias existing within African American beauty standards can be seen upon looking at Essence Magazine’s (a monthly magazine for African American women that covers fashion, lifestyle and beauty) “40th Anniversary 40 Most Beautiful Covers” piece. Out of the forty covers that this feature highlighted as the “Most Beautiful” in the history of Essence Magazine, only one presents a very dark-skinned African American woman – model Alek Wek – and her picture is displayed in black and white.

This is a clear-cut example of the sort of racially biased trends that consistently emerge, even within specifically targeted African American media. Despite the few exceptions made for “exotic” women, “the image of Black beauty in popular Black magazines gives the impression that Black… is only beautiful when it is altered” or somehow fits typical Western ideals (Sekayi 469; Thompson 847). It is shown, therefore, that in nearly every facet of media, African American women are told to strive for this nearly unattainable ideal. This pervasiveness of generally one specific type of African American beauty “impacts African American women, because it is often not [their] image that becomes the vision and standard of beauty” (Thompson 849).

Upon examining these standards of beauty that are presented for African American women, it is important to now address how these public and media images influence the personal identities of many African American women. This unspoken, yet ubiquitous hierarchy among people of color results in serious consequences for some African American women with darker skin and “natural Black” hair. As Gordon points out, many Black girls “use images of Black women as their source of comparison” (Gordon 247). While one might guess that this source of comparison would be less damaging than comparing to White women, the racial bias that similarly emerges in the prevailing images of African American women in the media can still be incredibly problematic to many African American women. Studies have shown that “exposure to idealized images of other women and, more specifically, African American women had an impact on Black women who reported being less satisfied with their bodies” (Frisby 342). In Dia Sekayi’s research on the effects of the Eurocentric standard of beauty on African American women, an overwhelming majority, 72.8%, expressed discomfort with the way the media defines beauty for Black women (Sekayi 474). This is detrimental, as these media portrayals leave a large group of African American women who don’t fit these ideals to feel undesirable, unwanted or unattractive. The images of famous African American woman who have been constructed – usually through either physical or digital alteration – to fit Westernized ideals produce the controversial question of why being “just black” isn’t good enough. Or, more specifically, why certain types of “black” are better than others. There are many personal costs of beauty standards that define dark skin and “natural Black” hair as inherently and automatically problematic.

The large majority of African American women “accept the Eurocentric standard as reality and understand that whether or not they embrace it as their own, they will be judged according to it” (Sekayi 474). This can be incredibly destructive to African American women who do not fit the typical image of “beauty” endorsed by the larger culture. While body image is molded by both external and internal sources of validation, these two sources often go hand-in-hand (Stephens & Few 253). As one woman in the documentary film Dark Girls states “when you live so many years with people having certain judgments relative to your skin tone, you start to believe it” (Dark Girls). Other people’s beliefs about beauty affect many women’s view of themselves, as normative standards are used to evaluate one’s own level of attractiveness. The influence of Westernized African American media images is so great, that these standards have significant sociocultural affects not only on notions of physical attractiveness, but also on many African American women’s courtship, self-esteem, and identity. In Stephens and Few’s study on fifteen African American adolescents (seven boys and eight girls), 100% of the male participants chose the image of the Westernized African American woman (displaying long, straight hair and lighter skin) as the most beautiful and desirable image, while none of them said that the image of the Afrocentric woman (displaying darker skin and coarse hair) as beautiful or desirable (Stephens & Few 255-256). Certain phrases such as “color struck” and “bleaching syndrome” have been used to indicate “preference among some African Americans for lighter skinned mates as a means to ‘lighten up’ the family and achieve social status” (Stephens & Few 253).

African American women acknowledge that the dominant standard of beauty is Eurocentric, as one African American girl in A Girl Like Me states, “there are standards that are imposed upon us like, um, you know… you’re pretty, you’re prettier if you’re light-skinned” and another girl states how “you have to have straight hair, relaxed hair” (A Girl Like Me). These Eurocentric standards of beauty have become so internalized within the dominant society and the African American culture that even women who don’t fit these ideals but potentially have positive body image might have difficulties in finding a partner or feeling connected to certain Black communities. As one girl explains, “I felt like there was not any attention towards me because of maybe my skin color or because my hair was kinky” (A Girl Like Me). These notions based off of skin color and hair type leave many African American women feeling unaccepted, unattractive and unwanted, even by their own race, leaving many with problematic self-esteem issues.

While many women acknowledge their discomfort with the way the media defines beauty for Black women, many of them will still take drastic measures in attempts to align their appearance with these set beauty ideals. Hair treatments like weaves, relaxers and permanent chemical straighteners have become a normative part of Black beauty. As scholar Cheryl Thompson points out, covering up “natural tress and damaging [one’s] real hair for the sake of a desired ‘look’ should not be taken lightly” (854). Such hair practices can have serious negative affects on both the women’s natural-born hair and their self-image, feeling they must continuously use these practices in order to look beautiful. Although hair straightening practices are “tantamount to torture, Black women continue this practice because a ‘real’ woman has long straight hair, while short nappy hair is relegated to something children have or those women – according to mainstream and Black beauty standards – who may be deemed less attractive” (Thompson 848). Similarly, some African American women with very dark skin use skin bleaching creams or treatments in attempts to lighten their skin tone. As one women states, “I can remember being in the bathtub, asking my mom to put bleach in the water, so that my skin would be lighter, and so that I could escape the feelings that I had about not being as beautiful, as acceptable, as loveable” (Dark Girls). The fact that some women feel pushed to such extremes to alter their appearance demonstrates the serious threats that our society’s internalization of strict standards of beauty poses.

Black women are unique in that they are asked not just to strive to attain mainstream standards of beauty, but to have such standards completely override their natural being (Thompson 854). Media message emphasize an incredibly rigid set of ideals that are so pervasive it is virtually impossible for women to avoid them. Many studies have been conducted to reveal the dangerous effects of such media images on many African American women’s self-esteem, particularly darker-skinned women with naturally coarse or “kinky” hair. While it is important to recognize that “women with low levels of body esteem did report lowered self-satisfaction with body esteem when exposed to physically attractive images of African American models”, it is crucial to recognize where the notion of what makes African American models “attractive” comes from (Frisby 323). The long history of a racial hierarchy began from the marginalization that certain African Americans faced during the period of slavery, and the separation of house versus field laborers. Since this period in history, Westernized ideals have become so internalized not only by the dominant society, but also by a large majority of the African American community itself. The subsequent negative effects on and practices taken up by many African American women who do not fit these standards of beauty are frightening. The perpetuation of media exhibiting images of almost exclusively one type of African American women (and even then whitewashing these images) is highly problematic. As a different 22 year old, African American woman on Harvard’s campus illuminates, “I feel like black women’s representation in the media usually falls into three categories. One is the white-washed, thin, light-skinned black female with European features and white, middle class values. The other would be the loud, dark skinned, larger woman who lives in Harlem and has a drug problem – this woman is never portrayed as a figure of beauty, though. The last one is the ‘exotic’-looking, hyper-sexualized woman from Africa. I think maintaining these stereotypes of black women and portraying black culture as a monolithic entity in general has negative externalities on both the black community and society as a whole”. Essentially, interventions that resist and deconstruct exclusive Westernized notions of beauty must be conveyed through popular culture with African American female role models who fall outside of the “typical” notions of beauty. Though the internalization of these standards of beauty runs deep, steps must be taken in order to de-stigmatize and include all forms of African American beauty that have historically been ostracized from the realm of beauty in nearly every facet of society.

Works Cited

A Girl Like Me. Dir. Kiri Davis. 2005. Film.

Baptist, Edward E. “”Cuffy,” “Fancy Maids,” and “One-Eyed Men”: Rape, Commodification, and the Domestic Slave Trade in the United States.” The American Historical Review 106.5 (2001): 1619-650. Print.

Bernstein, Robin. “The Scripts of Black Dolls”. Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights. New York: New York UP, 2011. Print.

Dark Girls. Dirs. Bill Duke, D. Channsin Berry. Urban Winter Entertainment and Duke Media Production, 2011.

Frisby, Cynthia M. “Does Race Matter? Effects of Idealized Images on African American Women’s Perceptions of Body Esteem.” Journal of Black Studies, 34. 3 (Jan., 2004): 323-347. Web. 11 Apr. 2012.

Gordon, Maya K. “Media Contributions To African American Girls’ Focus On Beauty And Appearance: Exploring The Consequences Of Sexual Objectification.” Psychology Of Women Quarterly 32.3 (2008): 245-256. Women’s Studies International. Web. 11 Apr. 2012.

Kerr, Audrey Elisa. “The Paper Bag Principle: Of the Myth and the Motion of Colorism.” The Paper Bag Principle: Class, Colorism, and Rumor and the Case of Black Washington, D.C. Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 2006. Print.

Sekayi, Dia. “Aesthetic Resistance to Commercial Influences: The Impact of the Eurocentric Beauty Standard on Black College Women.” The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 72, No. 4, Commercialism in the Lives of Children and Youth of Color: Education and Other Socialization Contexts (2003): 467-477. Web. 11 Apr. 2012.

Stephens, Dionne P. “The Effects of Images of African American Women in Hip Hop on Early Adolescents’ Attitudes Toward Physical Attractiveness and Interpersonal Relationships.” Sex Roles (2007) 56:251–264. Web. 11 Apr. 2012.

Thompson, Cheryl. “Black Women, Beauty, And Hair As A Matter Of Being.” Women’s Studies 38.8 (2009): 831-856. Women’s Studies International. Web. 11 Apr. 2012.